Terraced fields and landscapes

A pilot study by the cultural landscape research group at the Erfurt University of Applied Sciences

Vorwort

Die hier vorgestellten Ergebnisse der Pilotstudie „Digitaler Kulturlandschaftsatlas Thüringen“ – „Terrassenlandschaften“ zeigen die vielseitigen Möglichkeiten einer digitalen Präsentation, um Themen zur Kulturlandschaft anschaulicher, erlebbarer und damit zeitgemäßer zu vermitteln.

Herzlich gedankt sei den wissenschaftlichen Tutorinnen Carla Bömeke, Martha Kindig, Mara Amalia Schlenz und Sarah Schönheit für die umfangreichen Digitalisierungsarbeiten und für die Erstellung zahlreicher Diagramme und GIS-Karten. Besonderer Dank gebührt Frau M. Eng. Theresa Schäfer und Dipl.-Geoinf. Andreas Geier für die Entwicklung und Gestaltung unserer neuen Webseite einschließlich der interaktiven Animationen sowie der großformatigen Drohnenfotos und Videosequenzen. Die professionelle Gestaltung der Übersichtskarten lag ebenfalls in den Händen von M. Eng. Theresa Schäfer.

Ein wesentlicher Bestandteil des Terrassenprojektes sind die Detailstudien und Interviews über die Terrassenlandschaften in Gießübel und Jena. Der Ortschronist und Fotograf Gunter Heß in Gießübel und der Landschaftsarchitekt und Hobbywinzer Wolfram Stock in Jena halfen uns mit ihren fundierten regionalen Kenntnissen und Interviewbeiträgen, die sozial- und kulturgeschichtlichen Hintergründe dieser Terrassenlandschaften besser zu verstehen und allgemeinverständlich aufzuarbeiten. Wertvollste Beiträge lieferte Gunter Heß mit seinen einzigartigen historischen Fotoaufnahmen, die den Alltag in Gießübel über eine Zeitspanne von mehr als 100 Jahren dokumentieren.

Ohne die finanzielle Förderung durch die Thüringer Staatskanzlei (im Rahmen der Richtlinie zur Förderung von Kultur und Kunst) wäre die Durchführung der Studie durch unser Team an der FH Erfurt in dieser Form nicht möglich gewesen. Dafür sei ebenfalls ausdrücklich gedankt.

Prof. Dr. Ilke Marschall I Prof. Dr. Hans-Heinrich Meyer I Prof. Dr. Björn Machalett

Table of contents

- Relics of sustainable agriculture under extreme conditions

- Were terraces created actively and purposefully, or did they arise by chance?

- About "slope ledges" and "ski jumps"

- A look at the map: where are there terraces and why?

- On the influence of rocks and landforms

- Are there slope and elevation preferences?

- About the importance of the compass direction (exposure)

- How terraces and ownership are related

- How old are terraced fields?

- What was grown on the terraced fields?

- How many terraces once supported vine cultures?

- Only change is constant

- Disappeared and built over: Results of a current inventory

- Worth seeing: Current and historical terrace locations in Thuringia

- What are terraces worth to us and what can landscape maintenance and nature conservation contribute to their preservation?

- Picture gallery

- List of references

- Relics of sustainable agriculture under extreme conditions

„An den Berghängen liegen die Felder horizontal in langen Sätteln, terrassenförmig, durch Raine voneinander getrennt. Vereinzelt, wie in Kleinschmalkalden (gothaischer Anteil) und im Haselgrunde bei Steinbach-Hallenberg, verlaufen langgestreckte Pläne steil den Berg hinauf. Sie können nicht mehr gepflügt, sondern müssen von den Frauen mit der Hacke bearbeitet werden, auch wenn Anspannvieh zum Pflügen vorhanden ist." *

Terraced fields are artificially terraced landforms, of which there were once well over 10,000 in Thuringia. Most of them were still used for agriculture until the middle of the 20th century. Heavy physical work was part of everyday life. Like hardly any other element of the historical cultural landscape, terraced fields testify to a life full of deprivation with and from nature in the centuries before the introduction of mechanized agriculture.

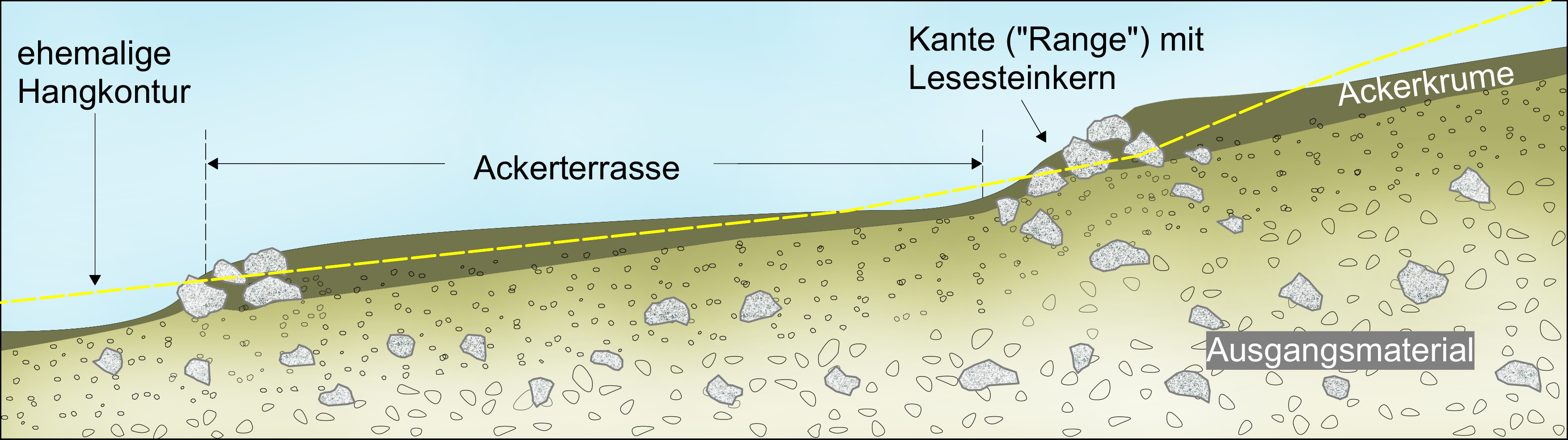

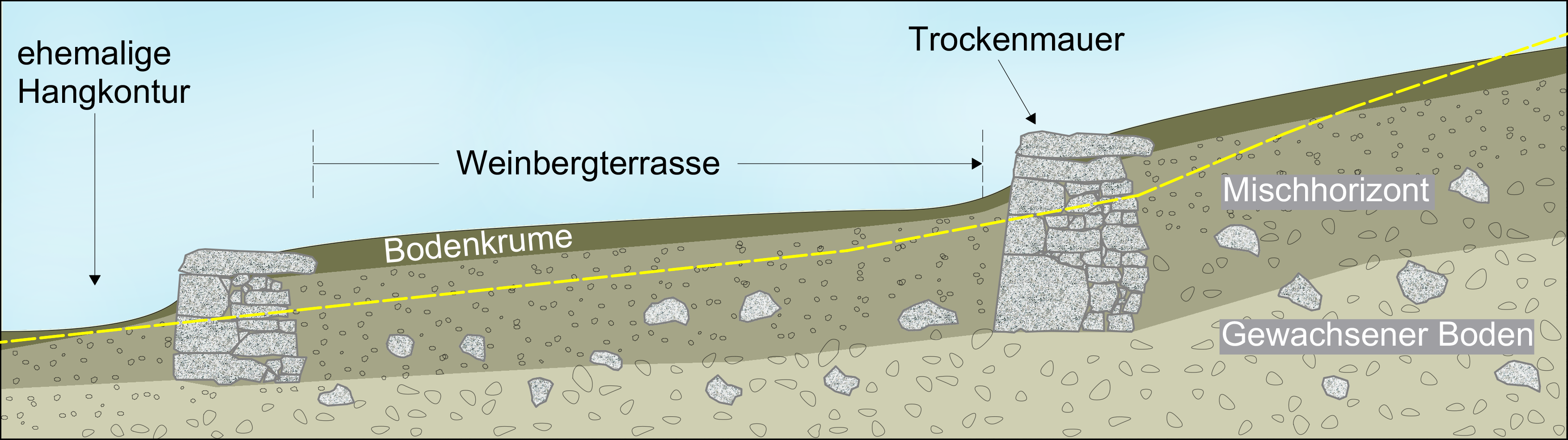

Terraced fields are defined as stairslike, flat areas on slopes ("terraces"), often only a few meters wide, which usually run more or less parallel to the contour lines. Downhill they are bordered by steps, which depending on the region are called “Ranken" or "Rangen", in technical terms "Stufenraine" ("Hangstufenraine", "Terrassenraine"). * As a rule, there are several terraces, both above and next to each other, so that entire slopes appear stepped.

The construction of terraces made it possible to cultivate hillsides in mountainous relief, where there was often only little arable land, which in an undeveloped state could only have been used as forest or pastureland. Terraces reduce soil erosion and improve the root penetration and fertility of the tilled soil. Terraces thus prove to be a historical example of particularly sustainable agriculture adapted to natural conditions.

Photo 1:

Ring of historical terraces in the surroundings of Heubach, district of Hildburghausen

Drone photo: A. Geier (7/2022)

- Were terraces created actively and purposefully, or did they arise by chance?

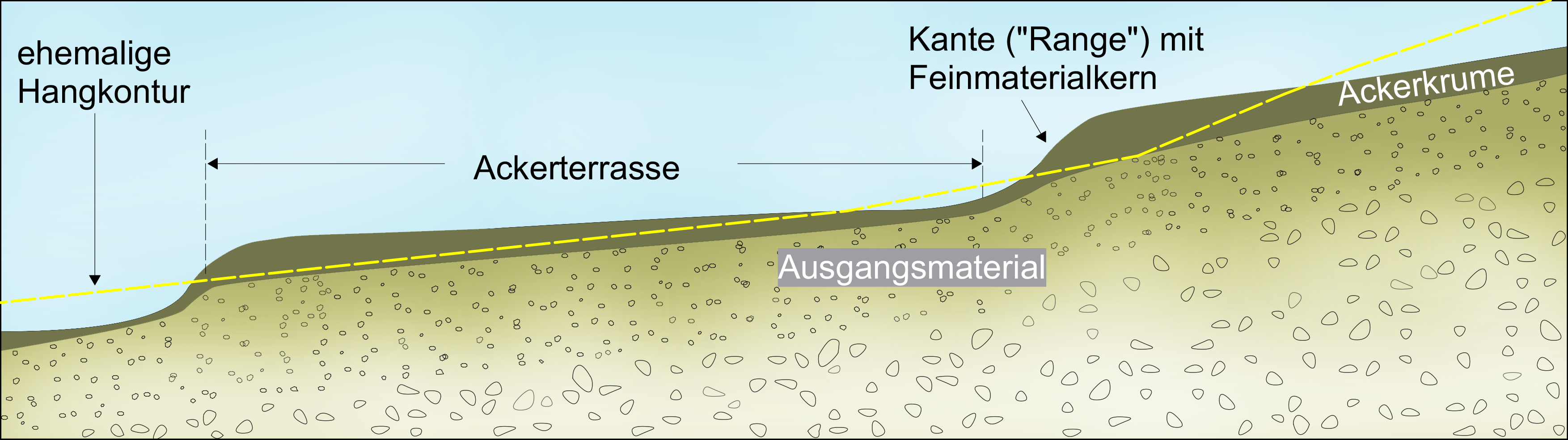

Fig. 1:

The three basic forms of historical terraces

- Terraces composed of fine-grained soil

Terraces of this type usually have a fairly flat slope in profile and consist mainly of the fine material of the humus rich topsoil. They have low steps and can have quite a large spatial depth (see Fig. 1 and photo 1, example Heubach).

The vast majority of terraces built of fine material can be traced back to a planned and active formation presumably. This is indicated by their mostly very regular and linear proportions. On the other hand, they often appear on a large scale and sometimes cover large areas of the village districts.

Certainly, however, the generation-long slope-parallel plowing and soil erosion contributed, so to speak, “all by itself” to the formation of stepped slope profiles.

The following quote from an essay by Friedrich Heusinger (1826) suggests that it was probably not common practice, but at least well known in theory how slopes could have been profiled with a certain plowing technique. With this "model" in mind terrace steps would then be a technical partial effect of tillage.

- Exkurs: „Dann ist weiter nichts zu thun..."

„Dann ist weiter nichts zu thun, als daß der Pflüger von der tiefsten Furche zu ackern anfängt, und zwar immer nur so einsetzt, daß ihm der Berg oder die höhere Stelle seines Ackers zur linken Hand bleibt, denn bey der Bauart unseres gemeinen Pfluges, wo immer die aufgeackerte Erde auf die rechte Seite des hinter dem Pfluge stehenden Pflügers umgelegt wird, werden alle Furchen von der Höhe zur Tiefe umgewendet, wodurch denn geschiehet, daß das Erdreich schon nach dem ersten Ackern an der untersten Gränze, wo sich der Terrassendamm bilden soll, erhöhet, die obere Gränze jedoch um eine Furche breit entblößet wird. Wenn der Ackerboden eine Zeit lang gelegen hat, so wird er geegget, und bald darauf, wenn etwa ein Regen gefallen war, und das Erdreich wieder oben abgetrocknet ist, wird mit einem breiten langstieligen eisernen Rechen quer über gegen die untere Gränze zu alles abgerechet, was an Steinen und harten Erdklösen auf dem Acker liegt, um dieses in den Böschungsdamm zu bringen. Nunmehr kann der Acker mit einer Sommerfrucht bepflanzet und besäet werden. ... In Ansehung der Dungstoffe oder Verbesserungsmittel, welche dem Acker etwa beygebracht werden sollen, ist zu bemerken, dass dieselben größtenteils auf diejenige Hälfte des Ackerbeetes, welche bisher höher lag, gebracht werden muß, denn durch das mehrmals wiederholte Anackern der obern Erde gegen die untere Seite in der Nähe des Böschungsdammes wird die letztere an und für sich schon gut und fruchtbar, aber die obere Seite wird immer mehr seiner guten Erde beraubt und muß Ersatz dafür bekommen“. *

It is interesting to note Heusinger's comment that downslope plowing would over time lead to the humus-rich topsoil being shifted downslopes, with reduced yields as consequence. In agricultural practice, this was actually counteracted by fertilizing with manure, litter, gypsum and other organic and mineral substances.

Photo 2 & 3:

Photos: A. Geier and T. Schäfer (7/2022)

- Terraces with a step composed of boulders

In the case of stony subsoil, the formation of step areas could be supported by plowing and successive laying of stones on the valley side or the plot boundary. In this way, the so-called "Steinrangen" (stone ranges) were created, terrain steps made of cores of collected boulders, on which the fine material plowed and washed away from the fields was deposited more and more over the years. Many historical terraces in Thuringia have such stony cores, even if they are not always visible at first glance due to woody (coppice) succession and later soil sedimentation.

There is no sharp demarcation from the terraces with a dominant portion of fine earth; rather, the transitions in the landscape are fluid, depending on how numerous the coarse components (“Lesesteinen”) are in the near-surface subsoil. Terraces with cores of clearing stone occur mainly in weathering layers and flow soils rich in coarse material, which cover the solid rock in varying thicknesses everywhere in Thuringia. The amount and form of the material to be read vary greatly depending on the substrate. They then decisively determine the morphological characteristics and the use of the high plains. Steinrangen were often left to the succession and today are usually characterized by woody bars.

Photo 4:

Terraces with steps of rock debris on the Sommerberg in Gießübel (district Hildburghausen)

Drone photo: A. Geier (7/2022)

- Terraces with stonewalls

On steeper slopes with incomplete soil cover, the terrace steps had to be built in a very laborious manner. On the one hand, this was done in order to convert the long and steep natural profile into several smaller sections with less inclination, and on the other hand to accumulate sufficient fine soil that could take roots. As a rule, this effort is only worthwhile for intensive crops such as viticulture. To do this, quarry stones had to be brought in suitably hewn sizes and then piled up to form stone walls. The small local quarries from which the building material came are often still preserved in the immediate vicinity of the historic vineyards.

Stacking the dry stone walls was a very demanding and laborious craft. Since the stones are not fastened with mortar, they had to be stacked closely and interlocked with the largest possible contact surfaces and at the same time tilted slightly inwards to absorb the pressure on the slope. In addition, the walls had to rest on the solid bedrock. A backing provided additional stability. Such walls have endured for centuries due to their impressive stability and are still visually appealing today. *

Once the walls were erected, additional fine soil and manure was brought in as needed and evenly distributed using hoes and karst (tridents). This application was then dug up to a depth of 1 m together with the subsoil and mixed ("rigolt"), resulting in a profoundly humus-rich mixed horizon with good root penetration. *

The large amount of work and material that was necessary for the preparation of the dry stonework was probably only accepted if an economic advantage was promised. This effort was not worthwhile for other agricultural uses. The economic argument weighed all the more since the natural limitations caused by the terracing of the valley slopes were by no means completely abolished, but at best mitigated. As a rule, the yield values of the German Bodenschätzung on terraces vary between 20-30 points (out of 100). This means, they are far from the level of good arable soils. Under today's economic conditions, arable farming on these areas is therefore no longer profitable (see numerous detailed examples).

Photo 5 & 6:

Vineyard terraces with dry stonework on the Jenzig (left) and dry stonework on an old vineyard cottage on the Sonnenberge, both in Jena

Photos: I. Marschall and H.-H. Meyer (7/2015)

- About "slope ledges" and "ski jumps"

Beyond the occurrence of the three basic forms presented above, terraces of very different proportions and dimensions exist in Thuringia. For example, the length/width ratios vary from narrow, ledge-like, contour-parallel bands to short, compact units with ski-jump-like steps. The length of terrace ledges can range from a few meters to several hundred meters. Such enormous lengths can be found above all in the areas of the “Long stripe fields“ and “Gelängefluren” of the Thuringian Forest and the Thuringian Slate Mountains (e.g. in Heubach near Masserberg over 600 m a.s.l.; see also map interpretation Wildenspring, photo 7). The spatial depths vary from only 2 m (!) to several decametres.

Photo 7:

Terraced long stripe fields on the Beerberg in Wildenspring (Ilm-Kreis). Basement rock: Quartzitic sandstone

Drone photo: A. Geier (7/2022)

The step heights also vary greatly. The steps are generally higher on steep slopes to minimize the angle of inclination of the terrace surfaces, and correspondingly lower on flatter terrain. The length of time the fields were used could also have had an influence on the height of the steps, in that more fine soil and stones were piled up down the slope the longer a terrace was tilled. As a result, the step heights in the majority of the Thuringian terraces today vary between 1 and 3 m, sometimes significantly more (maximum: 8-10 m in Gießübel in the Slate Mountains with a terrace depth of 20-25 m; see also photo 8 and 9).

Photo 8 & 9:

Terraces with high steps on the Sommerberg in Gießübel (left) and terrace steps with low height on the Löffelberg in Gießübel, district of Hildburghausen (right)

Photos: T. Schäfer and A. Geier (7/2022)

- A look at the map: where are there terraces and why?

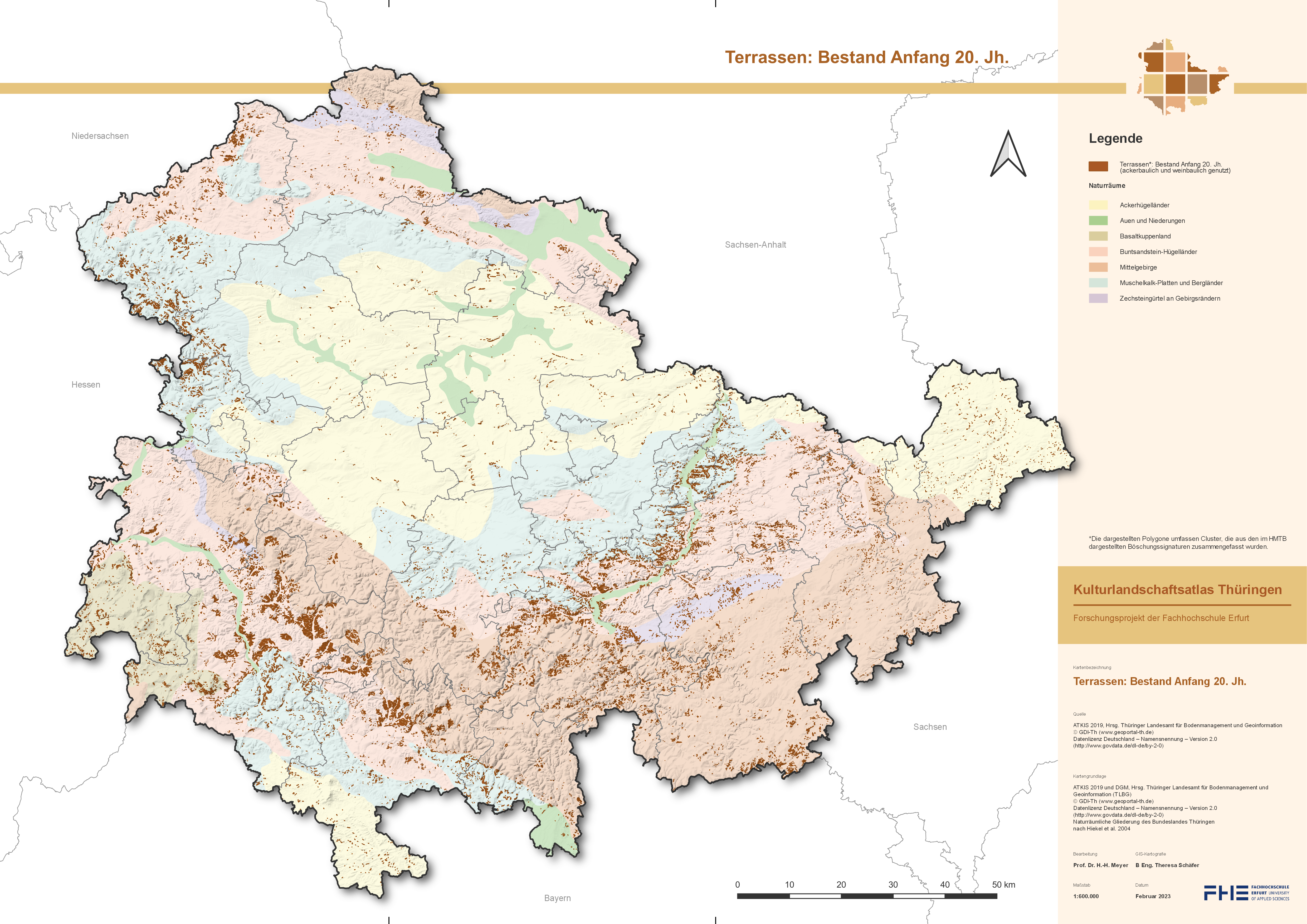

Terraced areas occur in Thuringia in many natural areas, but in very different forms and densities. Above all, they are concentrated in the Thuringian Forest and in the western part of the Thuringian Slate Mountains (Schwarza-Sormitz area), in southern Thuringia in the “Buntsandsteinland” and occasionally in the “Vorderrhön” and on both sides of the middle Saale valley between Rudolstadt and Jena. In northern Thuringia, the “Werrabergland” and the “Eichsfeld” are priority areas. In the following we will have a look on the causes of this conspicuous spatial disparity.

Fig. 2:

Terraces in Thuringia existing at the beginning of the 20th century

Quellen: Hist. Messtischblätter 1 : 25 000 und DGM2 ©GDI-Th

- On the influence of rocks and landforms

From a geological point of view, terraces can be found on a wide variety of subsoil. Statistically, however, they are common in special formations (Fig. 3). Almost half of all terrace areas are created in Buntsandstein rocks, another good fifth in Paleozoic and older rocks. This conspicuous dominance can be explained primarily by the fact that the terraces are concentrated in the Thuringian Forest, in the Slate Mountains and in their foothills, i.e. regions where these rocks are particularly widespread. For morphologic reasons, the pressure here to create terraced fields was the highest in Thuringia.

No Data Found

Fig. 3:

Shares of the Thuringian terrace area in the different geological formations [in %]

On closer inspection, however, it also becomes apparent that the different morphological hardness of the rocks, i.e. the resistance to plowing or construction, obviously only had a secondary influence on the distribution of terraces. This becomes clear when one compares the soft clay and marlstones of the Lower Buntsandstein and the Röt (Upper Buntsandstein) with the sandstone-dominated, harder layers of the Middle Buntsandstein (Fig. 4). The morphologically softer clay and marl rocks are terraced only slightly more frequently than the harder sandstone slopes of the Middle Buntsandstein. And even the dry and stony limestone slopes of the Muschelkalk are covered by terrace ledges, even though much more rarely than the red sandstone slopes. However, the morphologically somewhat softer marlstones of the middle Muschelkalk are also dominant here. Terraces literally cling to the rugged, jagged gypsum rocks of the Keuper and Zechstein mountains at the Schwellenburg near Erfurt and in the Orla valley.

In the slate mountains, terraces often cover the loamy and gently undulating slate and greywacke weathered soils. The terracing was relatively easy to carry out there, but these terraces were then also very easy to level, so that the later losses here are particularly large.

In the Thuringian Forest, distinctive terraced areas are widespread on porphyries, conglomerates, sandstone and claystone of the Rotliegend, i.e. on hard and softer rocks alike.

Terraces can even be found locally in loose rock: on soft loam and gravel sediments of the higher quaternary river terraces of the Middle Saale Valley as well as on the Ice Age loess and boulder loam flats of the Thuringian Basin and the Altenburger Land.

Less common are terraced fields in the Keuper hill country and the river valleys of the Thuringian basin, where there was no pressure to expand the farmland into the few steep slopes that existed there. Steep hillsides have only been used as vineyards since the High Middle Ages, as can be seen in the example of the “Schwellenburg” mentioned above or the “Roter Berg” in the north of Erfurt. In prominent valley cuts (e.g. Unstrut valley, Wipper incision) isolated terraces developed, especially on sun-exposed slopes, probably mostly on old vineyards.

No Data Found

Fig. 4:

Shares of the terraced area in the detailed stratigraphic units [in area %]

The scarcity of terraces on the shell limestone plateaus can be explained in a comparatively simple manner. Here, flat arable areas without the need for terracing alternate with steeply sloping edges, which, because of their shallow, rocky soils, were left to climbing goats and sheep for centuries as grazing areas. There are also many former vineyards close to villages, as well as isolated areas of arable terraces (e.g. in the “Reinstädter Grund” and in the “Hexengrund”, two side valleys of the Middle Saale).

In summary, the distribution of the Thuringian terraces is by no means solely dominated by the geological subsoil, as one might initially assume. Rather, the prevailing landscape relief influenced the distribution of arable terraces much more than the geological subsoil. Especially in the narrow mountain valleys Terrace construction was typical of the local landscape. Wherever there were only very limited arable land resources available, terracing was essential for survival: This applies to many valleys of the Thuringian Forest, the deeply incised river systems of Schwarza and Sormitz (Thuringian Slate Mountains), to the valley flanks of the Middle Saale and its tributaries and to the Werra and its side valleys in western Thuringia and in the Obereichsfeld.

Photo 10:

Historic vineyard terraces on the Schwellenburg, a Gipskeuper hill north-west of Erfurt

Drone photo: A. Geier (7/2022)

- Are there slope and elevation preferences?

Answers to these two important questions should help to clarify whether and to what extent technical-related and climatic aspects of the terrain, which result specifically from the slope gradient and the altitude, were taken into account when creating terraces. Indirect conclusions can then be drawn about possible historical uses.

The question of the prevailing gradients of terraced slopes in Thuringia should be taken up first. The issue here is not the gradient of the individual step and surface elements, but the inclination of the slope areas as a whole, on which the terrace relief was later created. In this context, the question would also have to be answered as to what limit values for inclination slopes in pre-industrial agriculture could have been cultivated without terracing at all, i.e. from which limit area terrace construction makes economic sense and when it was imperative.

The statistical evaluation of a medium-resolution digital terrain model (DGM25) can provide answers.

No Data Found

Fig. 5:

Slope preferences of the historical terraces [in area %]

Wie das Diagramm zeigt (Abb. 5), sind in Thüringen fast drei Viertel aller historischen Terrassen auf Standorten mit weniger als 25 % Hanggefälle angelegt worden, also auf Hängen geringer bis mäßiger Neigung; nur ein kleinerer Teil liegt auf steilen Hängen mit 25 % bis rd. 50 % Gefälle. Vergleicht man diese Grenzwerte mit den empirischen Grenzwerten der heute gängigen landwirtschaftlichen Praxis, so zeigt sich ein interessantes Ergebnis: Nach dem aktuellen Wissensstand kann Getreide bei hangparalleler Bewirtschaftung maschinell bis zu Neigungen von 20 % angebaut und abgeerntet werden, Kartoffeln bis zu 10 %, bei Bearbeitung in der Fallinie liegen die maximalen Hangneigungen jeweils leicht höher (Tab. 1). Nicht mehr beherrschbar sind dagegen bei Getreide alle Hangneigungen über 30 % bzw. bei Kartoffeln ab 20 %. Neigungen über diesen Grenzwerten würden die maschinelle Bearbeitbarkeit übersteigen und gleichzeitig das Risiko der Erosionsgefährdung signifikant erhöhen.

|

Fruchtart

|

maschinentechnisch beherrschbar

|

maschinentechnisch erschwert beherrschbar

|

maschinentechnisch nicht mehr beherrschbar

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Schichtlinie

|

Falllinie

|

Schichtlinie

|

Falllinie

|

Schichtlinie

|

Falllinie

|

|

Getreide

|

0-20 %

|

0-25 %

|

21-28 %

|

26-30 %

|

über 28 %

|

über 30 %

|

|

Kartoffeln

|

0-10 %

|

0-12 %

|

11-20 %

|

13-18 %

|

über 20 %

|

über 18 %

|

Table 1:

Now, a significant proportion (40 %) of the historic terraces are still below the 20 % corn slope limit, so the question arises, why were they terraced anyway?

There were practical reasons for this. On the one hand, the progressively increasing need for tractive power and the turning ability made it difficult to manage even on moderately steep slopes. Since only rich farmers could afford strong oxen or horses as draft animals, many households were left with only dairy cows as draft animals. At best, goats could be used as a lead for handcarts.

One answer for the terracing of flatter slopes could also be found in the fact that the cultivation of root crops in the Thuringian terraced villages played a major role. At first, beet cultivation dominated, but from the 19th century the potato rose to become the most important food and fodder crop. But root crops significantly increase the risk of soil erosion. Only very late after sowing do they guarantee adequate ground cover, which can be considered effective protection against soil erosion. For this reason, terracing was also required below the slope limit of 20 %.

The farmers were certainly aware that the steeper the slope, the more shallow and stony the soil, and that as a result it could also absorb fewer nutrients and water. They probably also knew that these soils dry out more quickly when there is little rain and are more subject to erosion when it rains heavily. They should also have noticed that the latent washing away of the humus layer over time led to a gradual reduction in soil fertility.

The farmers of the pre-industrial era were contemporary witnesses and observers of these events and their consequences. There is still evidence of severe soil erosion in many places in Thuringia. Probably the most striking are the deeply cut hollow ways and erosion ditches, which are often found in the immediate vicinity of old terraced fields. According to the current state of science, they are said to have been caused by catastrophic heavy and continuous rain since the Middle Ages and favored by increasing deforestation and cultivation (see many detailed examples). Against the background of these natural hazards, terracing opened up the possibility of establishing arable farming on a sustainable basis, even on sites at risk of erosion.

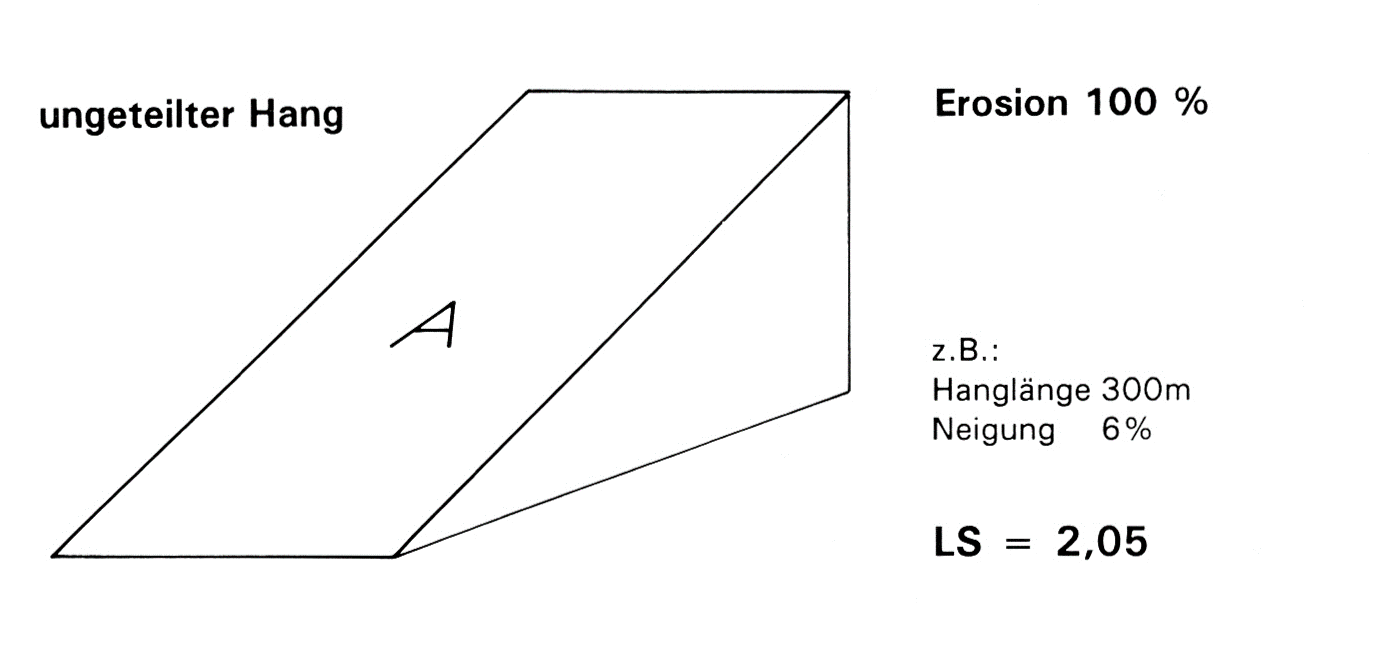

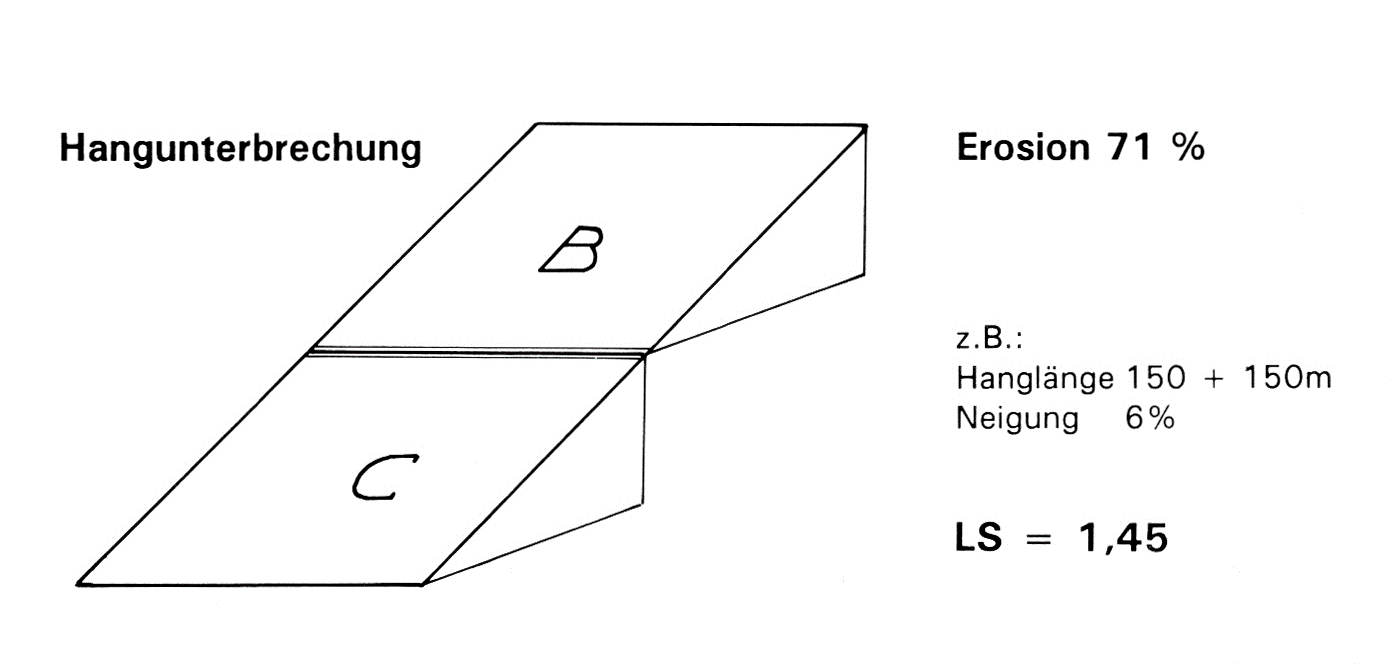

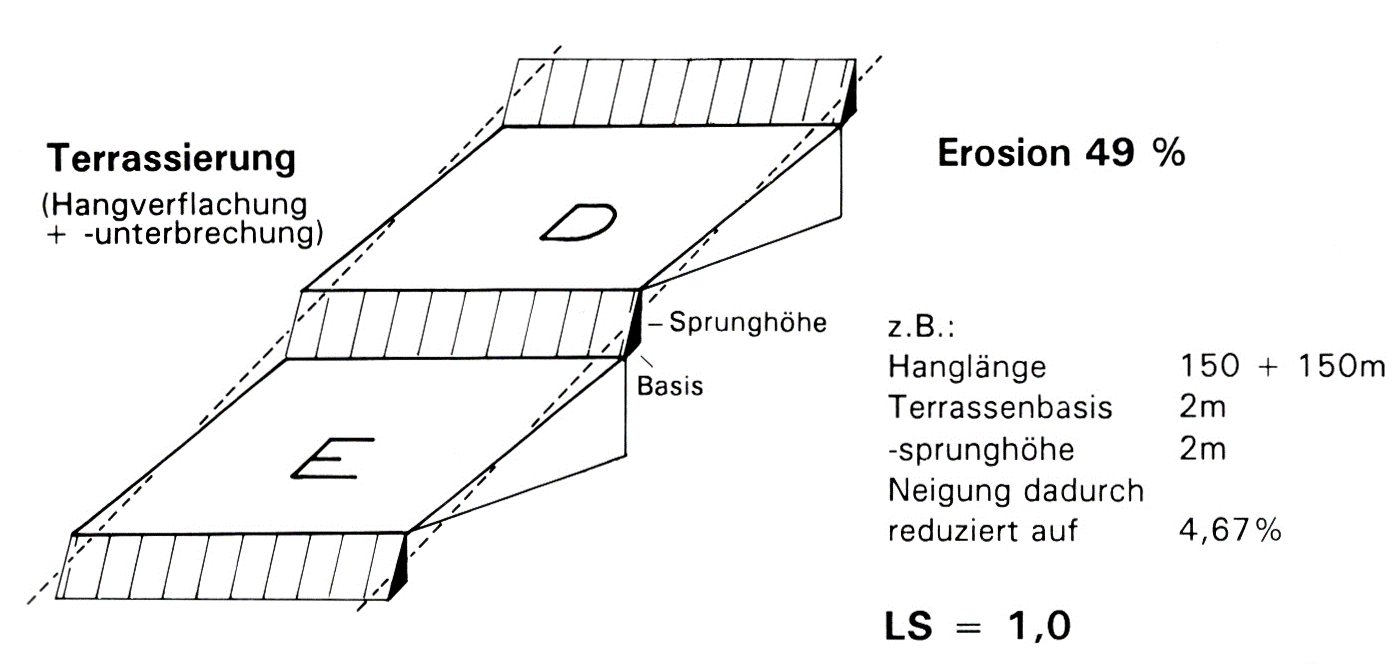

Allgemeine Bodenabtragsgleichung (ACAB):

(A)nnual soil loss [t/ha] = R (ainfall erosivity factor) • K (soil erodibility factor • L (Length) • S (Slope) • C (Crop) • P (direction of plowing) *

The lasting effect of terracing on reducing soil erosion can also be calculated using the so-called general soil erosion equation. It is known from empirical studies that, in addition to a number of other factors, the slope angle (“slope factor”) and the length of the slope (“L factor”) also influence the amount of soil erosion. If, for example, the slope or slope length factor doubles (both can be found in tables), the amount of soil removed also doubles. It should be noted that the slope factor does not increase linearly, but exponentially with the gradient of the slope. As a countermeasure, the gradient of the slope (slope factor) can be reduced in a targeted manner with terracing and the length of the slope can be very effectively shortened by the interposition of steps (see Fig. 6).

By the way, today's agricultural practice has not been able to significantly shift the natural processing limits through the use of modern agricultural technology, but rather has once again shown the economic consequences and the sensitivity of nature (danger of tipping over, limited plowing depth, increasing fuel costs, soil erosion, nutrient leaching, etc.).

1) Undivided slope

2) Slope disruption

3) Terracing

Fig. 6:

Influence of slope gradient and slope length

MÜLLER, J. (1996)

Finally, the question of the maximum height limit of the historical terracing has to be clarified. Such a border or border area cannot be defined with certainty in Thuringia. In terms of climate, potato cultivation would probably have been possible in all hilltop settlements in the Thuringian mountains, even if one had to reckon with increased risks in the mountain villages, such as crop failures caused by frost or wet weather. Nevertheless, in some of the highest settlements in the Rennsteig region (e.g. Oberhof, Masserberg) terrace construction was hardly used, since the places are on plateau-like saddles near the ridge line of the Thuringian Forest (Rennsteig). There, the possibilities and necessities for terracing remained limited.

In contrast, terracing was unavoidable in the deep and narrow valleys of the Thuringian mountain range. This explains why well over half of the Thuringian terrace area belongs to the altitude levels between 300-400 m and 400-500 m a.s.l. (57 %). Terraces at the highest altitudes (600 to over 700 m), i.e. the Rennsteig region, account for just 5% of the total terrace area. The highest terraces in Thuringia were found in Oberhof (just over 800 m, no longer in existence today), in Schmiedefeld/Saalfeld am Rauhhügel (792 m), in Steinheid (783 m) and in Schmiedefeld a.R. (774 m).

No Data Found

Fig. 7:

Distribution of historical terraces as a function of elevation [in area %]

- About the importance of the compass direction (exposure)

No Data Found

Fig. 8:

The influence of the exposure on the spread of the terraces [in area %]

Fig. 8 shows the extent to which the compass direction (exposure) has influenced the distribution pattern of terraced areas. This includes the orientation towards the climatic elements sun and wind. Accordingly, all sky sectors are represented relatively evenly throughout Thuringia as a whole, which may be due to the fact that the slope exposures are also fairly evenly distributed across Thuringia. Obviously, one shouldn't be too picky about the terracing either. In view of the striking lack of arable land, unfavorable shady areas had to be terraced in many places (north, north-east), which is not surprising, especially in the valley villages of the Thuringian Forest. This step was undoubtedly made easier by the cultivation tradition of the forest villages, where the majority of the terraced fields were cultivated with the thermally less demanding crops of the mountains such as potatoes, rye, oats and turnips (see below). For wine growing (e.g. in the Saale valley) the preference is of course for the sun-rich south and south-west locations, even if there are exceptions there as well, as old vineyard names underline (“Himmelreich” vs. “Vinegar bottle”).

- How terraces and ownership are related

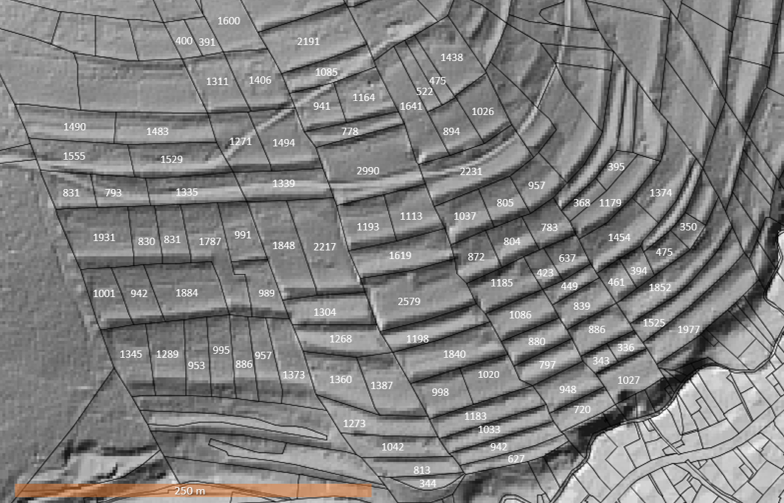

Fig. 9:

Historical field terraces and their ownership structure on the Sommerberg in Gießübel, Hildburghausen district (DGM2 superimposed with parcel boundaries and parcel sizes in m² according to ALKIS)

©GDI-Th (https://thueringenviewer.thueringen.de/thviewer)

The interaction between the shape of the terraced fields and the local ownership situation reveals the comparison of the high-resolution digital terrain model (DGM2) with a current cadastral map (ALKIS) (see Fig. 9). The relevant maps were simply superimposed in the GIS.

There is a remarkable correspondence between the morphological structure lines of the terraces and the plot boundaries: Almost all terraces coincide exactly with plots of land. In other words: A terrace unit usually represents an independent “ownership parcel”, i.e. it can be assigned to a specific property.

But there are also exceptions to this rule. For example, terraced (historical) vineyards on very steep slopes can be divided by more than one small terrace, each supported by elaborate dry stonework. In such a case, there is not just one, but several terraces on a property. The high intensity of use alone in combination with high-quality cultivation (wine) made the densely packed terrace construction profitable for the owner. Much more frequently, however, plots of land with several terrace units can have arisen as a result of later mergers and consolidations of small holdings (land clearing).

Video 1:

Terraced long stripes on the Beerberg in Wildenspring (Ilm-Kreis)

Drone video: A. Geier (7/2022)

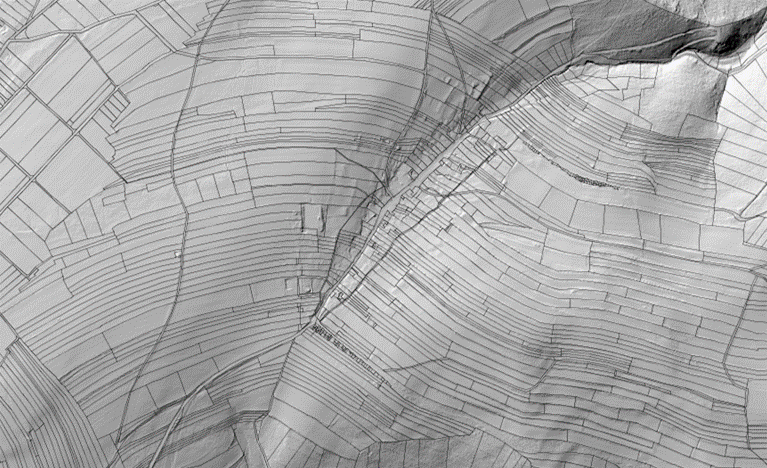

Fig. 10:

Terraced “Gelängeflur” in Wildenspring, Ilm-Kreis (DGM2 superimposed with parcel boundaries according to ALKIS)

©GDI-Th (https://thueringenviewer.thueringen.de/thviewer)

In addition to the local ownership situation, the regional settlement and field forms also had a major influence on the design of the terraced landscapes. It is about the shape of the individual parcels and their position and arrangement in the spatial network.

In principle, terraced areas can occur in all historical basic forms, in striped and block fields as well as in “Gewannfluren”. However, they are particularly common in long strips, the characteristic field forms of the high medieval clearings, here often in the context of row and street villages.

In the narrow long strips of the “Gelängefluren” typical of East Thuringia, they can form hundreds of meters long stepped lines and only a few meters wide terrace ledges, which then often meander through the landscape in an S-shape (e.g. Wildenspring, Ilm-Kreis; Fig. 10, Video 1). In the case of large broad strips, which, as former clearing strips, often stretch hundreds of meters uphill from the valley settlements, they form transverse units (e.g. Deesbach, district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt; Fig. 11).

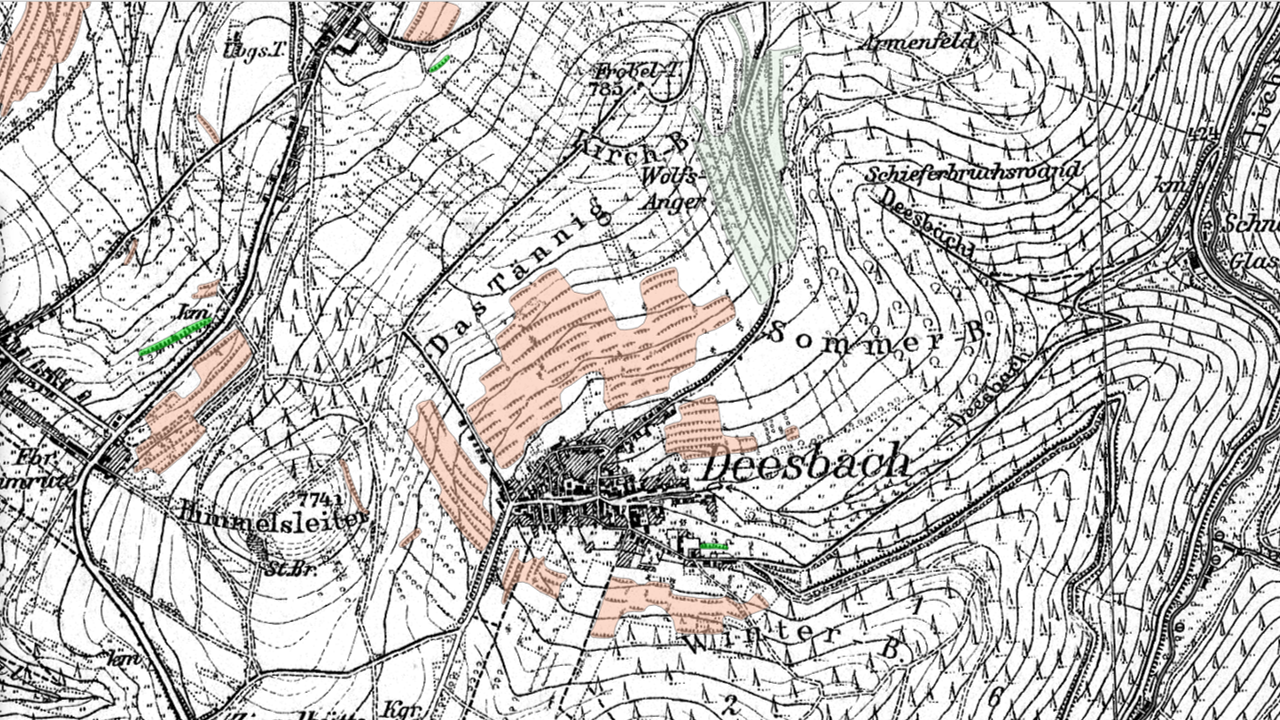

Fig. 11:

Step-like terraces in a medieval clearing with broad strips in Deesbach, district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt (DGM2 superimposed with parcel boundaries according to ALKIS)

©GDI-Th (https://thueringenviewer.thueringen.de/thviewer)

Fig. 12:

Extreme differences in exposure (shading) characterize the village location and the terraced landscape of Deesbach, district of Saalfeld-Rudolstadt (see also "Summer" and "Winterberg")

HMTB, 1903; ©GDI-T

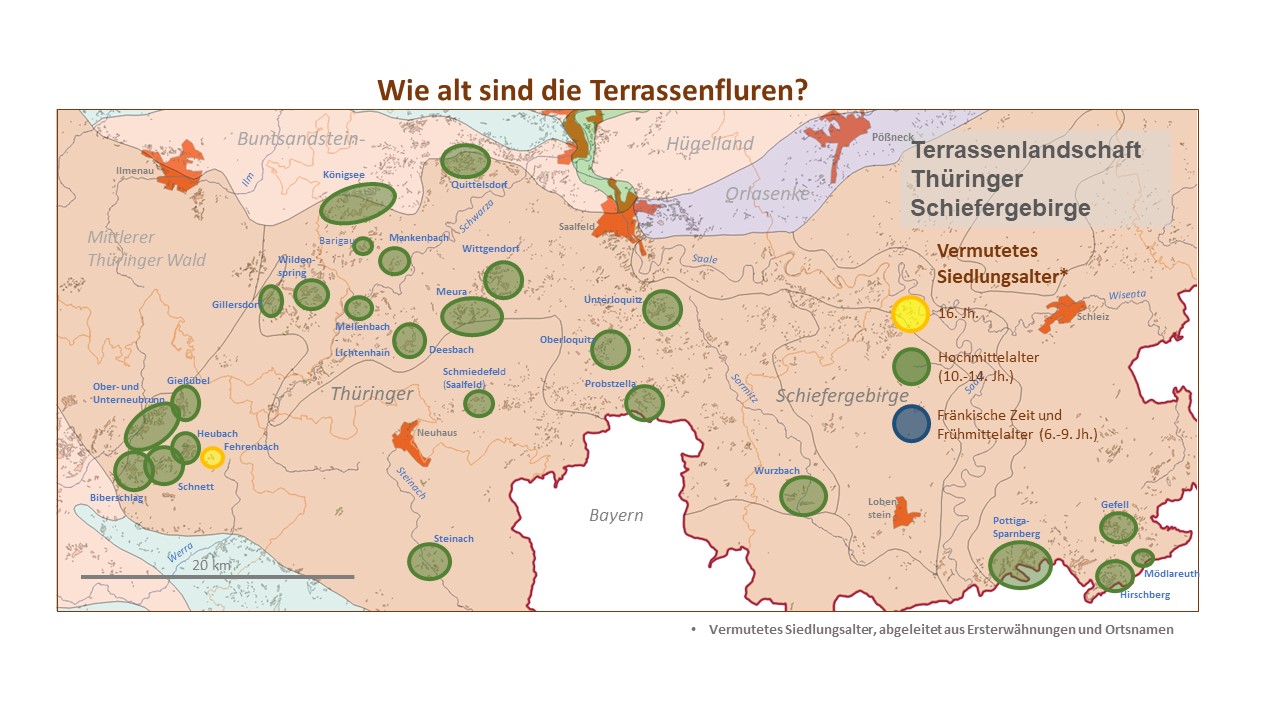

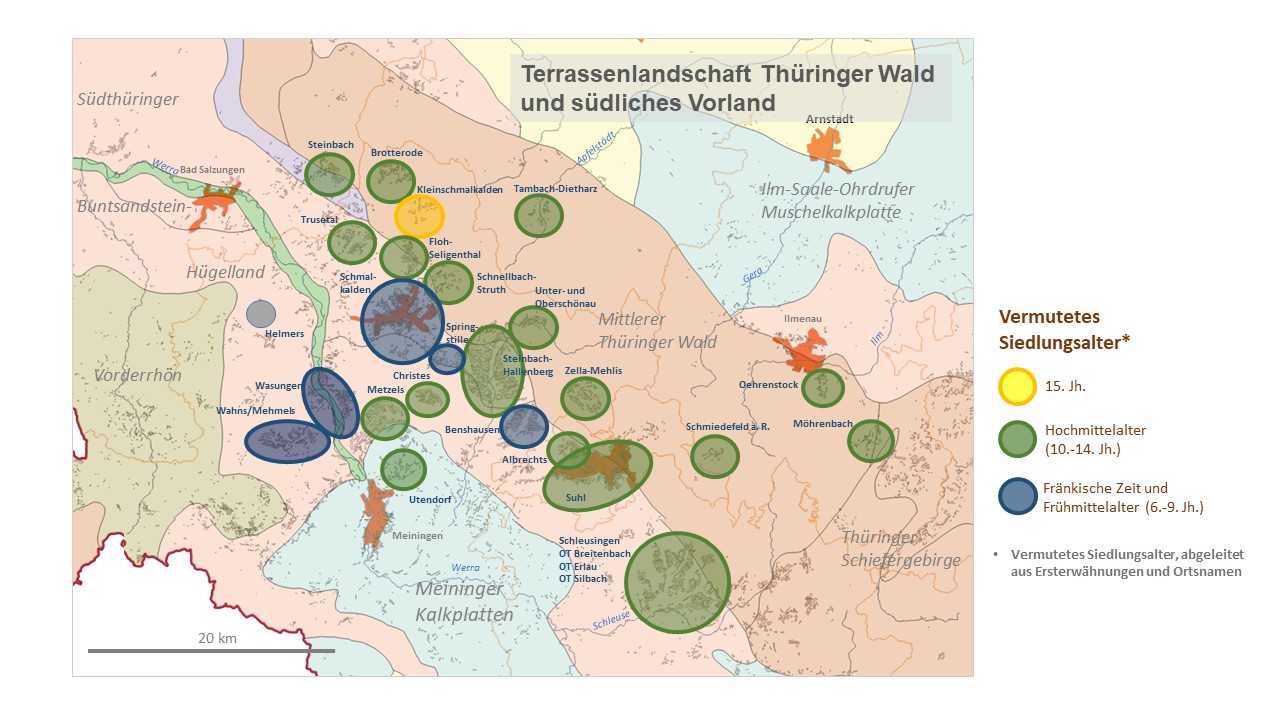

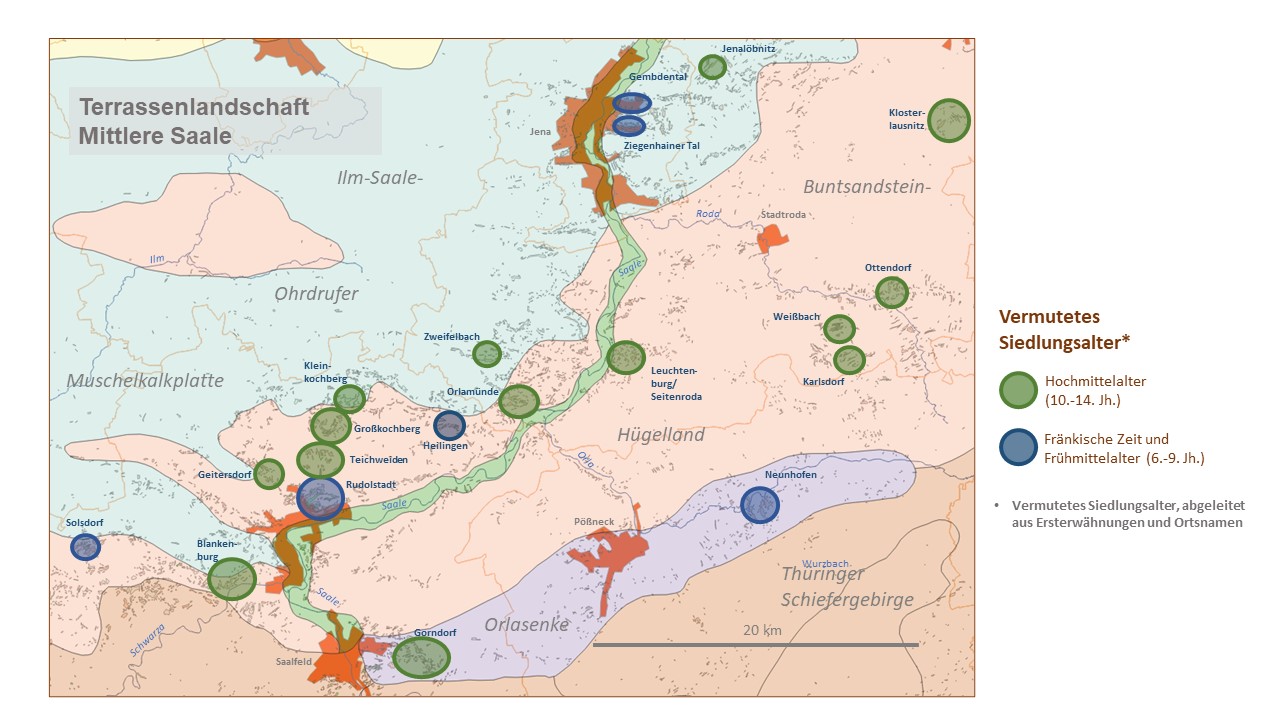

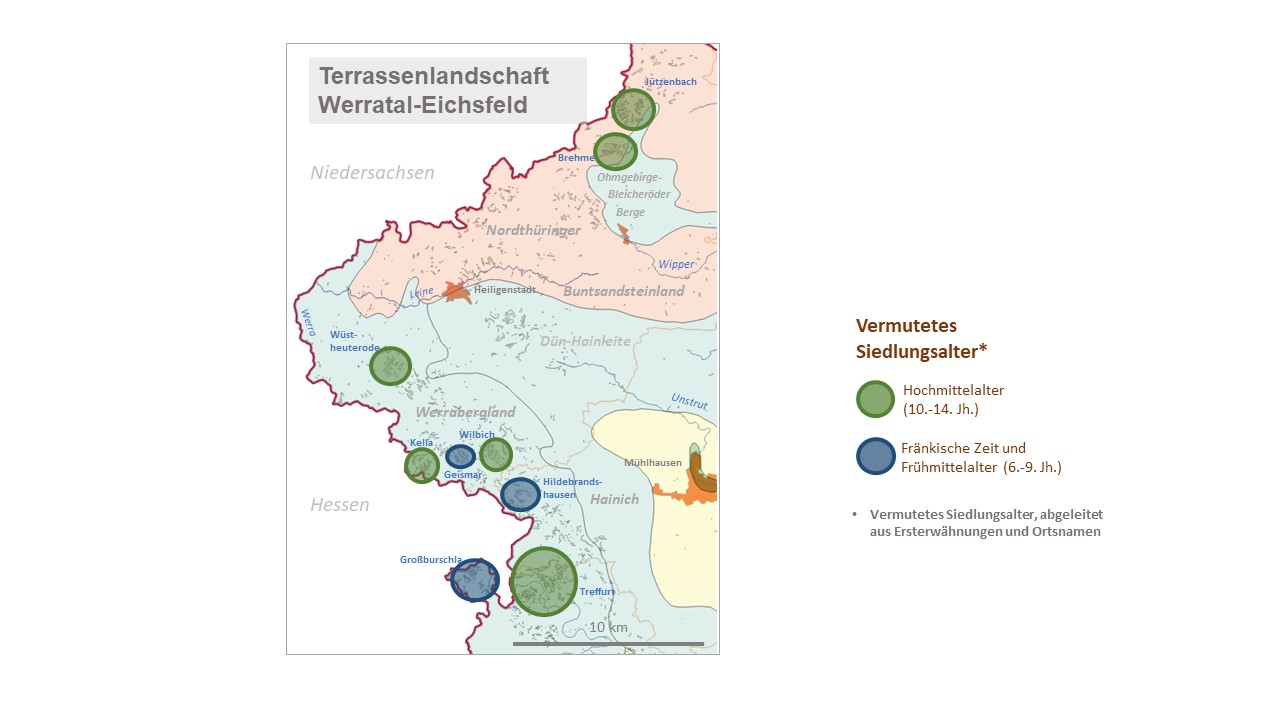

- How old are terraced fields?

The age of the terraced fields is difficult to determine, since terraces, as evidence of everyday culture, were hardly mentioned in early historical sources. Just as their shape and positional characteristics vary greatly, their age could also vary greatly.

For answering the exciting question of age, however, the settlement and field history findings mentioned above can provide interesting clues or at least contribute perspectives.

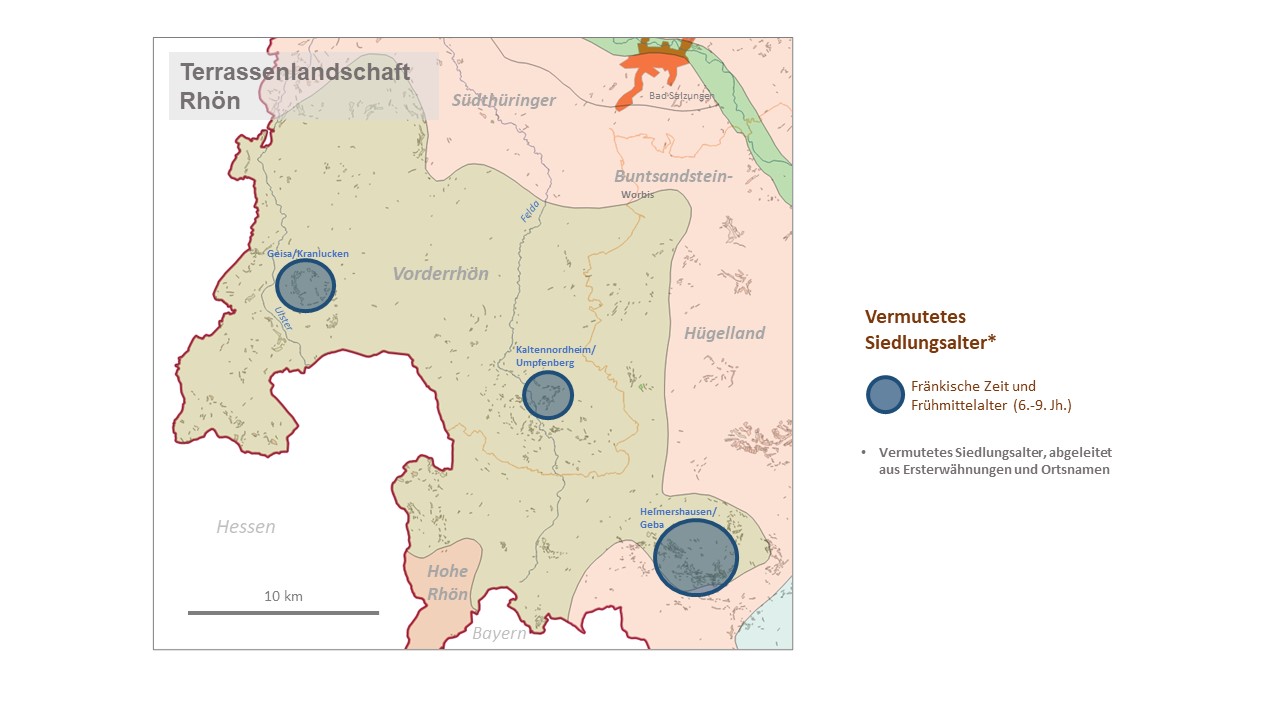

As already mentioned, many historic terrace fields appear in the spatial context of row and street villages. All these are planned settlement forms that were founded in regular patterns during the course of the high medieval clearing period (mainly 12th-14th centuries). They were initiated by the rulers of that time. During this period of strong population growth, settlement was increasingly extended to areas with poor soil (“marginal yield locations”). In particular, the sparsely populated forest areas at that time were cleared and gradually developed: the Thuringian Forest and its foothills, the plateaus of the Thuringian Slate Mountains, the valleys of the East Thuringian red sandstone hill country (“Holzland”) and the remote parts of the Eichsfeld. For most of the terrace villages in Thuringia, both the first documentary mentions and the place names typical of the time support a high medieval founding date. Certain places in prime locations such as the Werra and Saale valleys and in the Rhön are definitely older (early Middle Ages). The terracing in these places could also be older. Only further settlement-historical analyzes could bring about a clarification here.

Fig. 13:

Presumed settlement age of the detailed examples (derived from first mentions and place names) broken down by terraced landscapes

The large-scale colonization process was carried out by noble founding initiators, so-called locators, who commissioned knightly followers with the clearing of forests and new settlements on manorial land. In addition to the secular lords, the monasteries also played a role as carriers of the high medieval development of the country.

In the wake of the settlement, the basic structures of the field landscape were created almost at the same time. * The plot of land parceled out in the founding act specified the layout of the terraces, directly influenced by the relief conditions: in deeply eroded valley landscapes such as the Thuringian Forest, due to the extreme lack of arable soil, terracing was a basic requirement for long-term security of existence. Therefore, the idea of cultivating fields in terraced form could already have emanated from the aristocratic or ecclesiastical colonizers. Whether the great task of terracing was then enforced "from above" by official decisions as part of the founding process or whether it was only carried out voluntarily, individually and gradually, cannot be answered at the moment due to a lack of historical evidence. As the Gießübel case study suggests, the surveying challenges and the amount of work (costs) involved in the particularly demanding terracing will have been so great that in such a case only a coordinated joint effort would have led to success.

It is difficult to assess the influence of fragmentation of ownership in the course of inheritance divisions on the fragmented nature of terraced landscapes. Even if, for the reasons outlined above, a one-off joint effort is more likely, an asynchronous, successive development process cannot be ruled out in individual cases. It is generally known that the land system in Thuringia has become more and more fragmented over the centuries due to the widespread custom of “Realerbteilung” (division of land ownership equally among the heirs). Over time, this resulted in real estate, which in extreme cases consisted of many small and scattered plots of a few meters wide or long ("towel plots"). The extent to which the pattern of the terraces, which appears fragmented in many places, goes back in part to such inheritance divisions, i.e. to what extent terraces only emerged with the division of once larger plots, can only be clarified in the future with individual case studies of settlement history. However, it is easy to prove through the analysis of old deed books that repeated division of originally undivided terraces resulted in smaller elements.

- What was grown on the terraced fields?

After many studies on historical terraced fields, it is now certain that the historical terraces were once essentially cultivated as farmland or vineyards and were also used in this way for centuries.

Photo 11 & 12:

Field cultivation with a hoe in the 1950s (left) and potato harvest on rested soil in Rodeland

©Gunter Hess Collection, Gießübel

While the terrace areas themselves were tilled, the steps consisting of fine soil were mostly overgrown with grass. They were mowed once or twice, and grazed after the harvest. Stone ranges, on the other hand, often carried trees that were planted from time to time "on the stick" to obtain firewood as part of a coppice-like management. *

How one has to imagine cultivation on the terraced fields in the pre-industrial period, almost 200 years ago, and which crops were preferably cultivated on the terraces, can be illustrated by the following quote. It becomes clear, among other things, that there was probably no three-field farming on the terraced fields of the mountains, as is otherwise common in Thuringia, since the large number of livestock provided sufficient fertilizer. Nevertheless, a certain crop rotation with a strong dominance of the potato can be assumed.

„Ungeachtet der Ackerbau mit so manchen feindseligen Verhältnissen zu kämpfen hat, so findet er doch noch auf sehr bedeutenden Meereshöhen und stellenweise selbst noch nahe am höchsten Gebirgsrücken bei einer Meereshöhe von 2500 Fuß [fast 890 m, d. Verf.] statt, wiewohl freilich in sehr beschränktem Maße. Zwischen 2000 – 2500 Fuß Meereshöhe [oberhalb rd. 700 m, d. Verf.] ist der Feldbau fast bloß auf Kartoffeln, Hafer, etwas Lein und Kohlrüben beschränkt; zwischen 1800 – 2000 Fuß Meereshöhe [650-700 m, d. Verf.] baut man auch schon hie und da mehr Sommerroggen, auch wohl zuweilen Sommerwaizen, Gerste und Dinkel. Winterroggen und Waizen gedeihen nicht, theils wegen schlechter Beschaffenheit des Bodens, theils weil, wegen den strengen und lange anhaltenden Wintern, die Saat ausfriert. … Der Kleebau und der Anbau der Futtergewächse ist auf dem Th. W., bei dem Ueberflusse an Wiesen, weniger Bedürfniß … Bei dem ziemlichen Düngervorrath, den der bedeutende Viehstand liefert, können die wenigen Äcker meist nothdürftig gedüngt, und ohne Brache, Jahr aus Jahr ein, bebaut werden. Die Hauptfrucht auf dem Thüringer Walde ist die Kartoffel: fast jeder Einwohner baut seinen Bedarf auf eignem oder gepachtetem Lande. Jedes für sie passende Fleck, das hinreichendes mildes Erdreich hat, wird zur Cultur derselben benutzt, und wo der Pflug nicht gut anzuwenden ist, mit Hacke und Karst bearbeitet. … Auf vielen Äckern baut man alle Jahre nichts wie Kartoffeln und düngt dazu ein Jahr um‘s andere; anderwärts baut man 2 bis 3 Jahre hintereinander Kartoffeln und dann 1 Jahr Hafer oder Sommerroggen. Die im Thüringer Walde gebauten Kartoffeln sind vorzüglich wohlschmeckend und der gemeine Mann lebt größtenteils von diesem Gewächse. Sie werden zum Theil auch in Stücken geschnitten, die getrocknet gemahlen und mit Getraidemehl zu Brod verbacken werden. Der Lein gedeiht in dem feuchten Clima des Thüringer Waldes vorzüglich gut, nur wird der Saame nicht reif; der Flachs aber ist von vorzüglicher Qualität. Auch die Kohlrüben gedeihen noch auf den höchsten Punkten des Th. W., sie trotzen im Winter der Kälte und halten sich lange Zeit zum Gebrauch.“ *

The fact that turnips apparently took their place on the terraces before the introduction of the potato can be concluded from the following quote:

„Fragen muss man, womit sich die Waldbewohner erhalten haben, bevor sie die Kartoffeln kannten? Bejahrte Personen versichern, dass die Kohlrüben (Unter-Kohlrabi) einigermaasen ihre Stelle vertreten hätten, welche vormals häufig gebaut und selbst roh von den Waldbewohnern gegessen worden wären. Diese Frucht, die an Nahrungsstoff sowohl, als an Dauer, in Ansehung ihrer Aufbewahrung über Winter, weit hinter der Kartoffel zurückbleibt, wird auch noch jezt hier und da gebaut und als ein nüzliches Viehfutter geschäzt“. *

Beide Textauszüge spiegeln Nutzungstraditionen wider, die Jahrhunderte lang gepflegt wurden und bis in das 19. Jh. anhielten, bis die Technisierung der Landwirtschaft, die Einführung der Handelsdünger und neuer Formen des Fruchtwechsels auch in den Dörfern der Thüringer Gebirge Eingang fand. Diese Neuerungen konnten indes nicht verhindern, dass der Ackerbau auf den terrassierten Feldern zunehmend unwirtschaftlich wurde. An seine Stelle trat im Laufe des 20 Jh. mehr und mehr die Nutzung als Grünland, d. h. als ein- oder mehrschürige Wiesen oder als Rinderweiden, die mit den kleinteiligen und bodentechnisch schwierigen Standorten der Terrassen besser zu vereinbaren waren als der mechanisierte Ackerbau.

In klimatischen Gunstlagen, z. B. im Werra- und im Saaletal, ermöglichte zudem der Obstbau (Streuobst) eine Doppelnutzung auf denselben Flächen. Unter einer Baumschicht aus hochstämmigen Obstbäumen dehnten sich entweder pflegearme Mähwiesen oder Weiden aus („Streuobstwiesen“) oder Unterkulturen wie Futtergetreide, Gemüse, Kartoffeln oder Beerenobst, die noch bis in die erste Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts zur Erhöhung der Flächenerträge auf den ackerbaulichen Grenzstandorten häufig waren. * Regions without fruit growing worth mentioning included the higher terraced landscapes in the Thuringian Forest and in the Thuringian Slate Mountains, where there were only a few apple and plum trees in home gardens and areas close to the village, which mostly did not even ripen as a result of late frosts or cool weather. *

Photo 13:

Subsequent culture of orchards on historical field terraces on the Sandberg in Treffurt (Wartburg district)

Photo: H.-H. Meyer (8/2022)

- How many terraces once supported vine cultures?

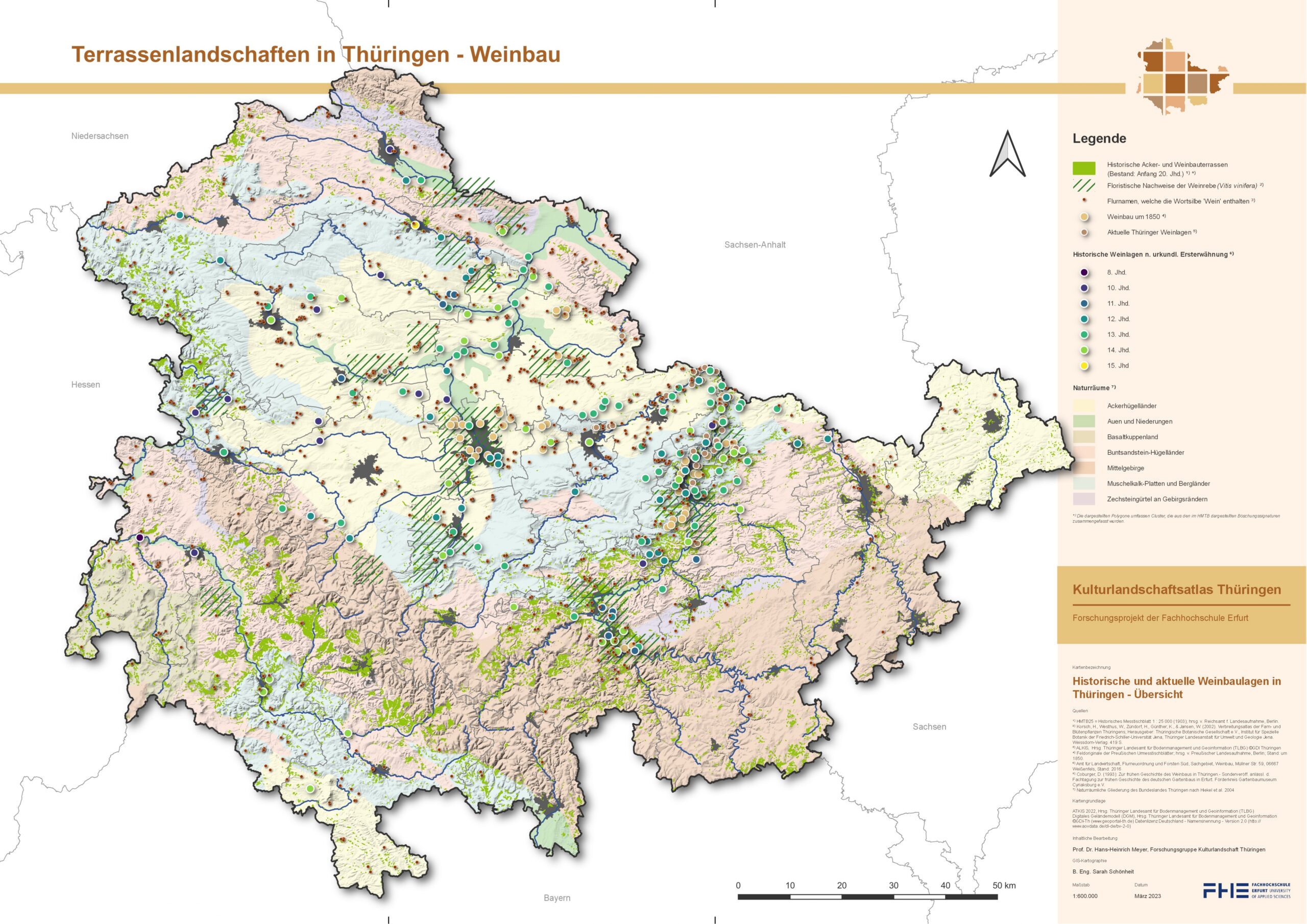

This question is closely linked to the earlier importance of viticulture in Thuringia. Today only a few are aware that Thuringia was one of the most important wine-growing regions in Germany in the late Middle Ages. Estimates assume that there were over 400, maybe even over 700 places in Thuringia that were once wine-growing. *

However, the total number of historic vineyards can hardly be ascertained today, because many of them have fallen into oblivion over the centuries because there are no longer any documentary mentions and no clear material legacies. Only a fraction of the former wine villages can be documented through historical sources. Even old toponyms (field names) that contain "wine" or similar wine-related syllables undoubtedly only incompletely depict historical viticulture; the same is certainly true for the floristic evidence of the grapevine Vitis vinifera, which has so far mainly been documented in the more intensively explored regions of Thuringia. The representations of vineyards in historical maps also represent only a fraction of all former vineyards. They are far too young and at best reflect the decline of viticulture in the 19th century.

Aware of this, the overview map (Fig. 14) can only give a very fragmentary impression of the maximum spread of viticulture in Thuringia. Nevertheless, it allows a vague assessment of the Thuringian regions in which vine cultures were once particularly widespread. This means that they were probably also more involved in the terrace cultures there. It should be noted that viticulture does not always require terrace construction, but that in many places non-terraced slopes and even flat areas were cleared up.

As a consequence of these considerations, terraced slopes, especially on the thermally favored slopes of the Thuringian Basin and the large river valleys such as the Middle Saale and Werra Valleys, are likely to have had an above-average frequency of vine cultivation. These do not necessarily have to be recognizable on elaborate dry stone walls * ; if not enough quarry stone material was available or if the financial and physical resources were not sufficient, the sophisticated dry stonework was not an option.

However, the map also shows that a considerable part of the terraced areas in Thuringia must have been used exclusively as arable land from the beginning, because the climatic conditions for viticulture were not met. For the higher elevations of the Thuringian Forest and the Slate Mountains, viticulture was not relevant even in the favorable climatic phase of the High Middle Ages.

Fig. 14:

Historical and current wine-growing locations in Thuringia

Quellen: Hist. Messtischblätter 1 : 25 000 und DGM2 ©GDI-Th

- Only change is constant

No Data Found

No Data Found

Fig. 15 & 16:

Use of the historical terraces at the beginning of the 20th century [in %] (left) and use of the historical terraces today [in %]

after HMTB of the German Reich; ed. by Reich Office for Land survey, Berlin and after ATKIS, ©GDI-Th

Spätestens in den 1950er und 1960er Jahren wurde der Ackerbau – wie oben schon erwähnt – als dominierende Form der Nutzung auf den Ackerterrassen immer mehr durch Grünland abgelöst. Mit der „Vergrünlandung“ veränderte sich das Landschaftsbild in den Thüringer Terrassendörfern gravierend. Der tiefgreifende Landschafts- und Nutzungswandel lässt sich besonders anhand historischer Postkarten und Luftbilder an vielen Beispielen veranschaulichen. Und er lässt sich statistisch belegen. Dies zeigt ein Vergleich der Flächennutzungen auf den Historischen Messtischblättern mit den Flächennutzungen auf der modernen digitalen Topographischen Karte (ATKIS) recht eindrucksvoll (Abb. 15 & 16).

At the beginning of the 20th century, for example, not all terraces were cultivated with crops, as was probably still the case in the early 19th century. Instead, the proportion of arable land had decreased to just 66 %, i.e. by a good third. In the same period, the proportion of unused areas, i.e. woody growth/succession, and newly created orchards had increased to a total of 28 %. At that time, many terrace areas had already fallen fallow, especially in remote and extreme locations. Farming and commercial fruit growing had found their way onto others. At the beginning of the 20th century, the proportion of grassland was still very weak (2 %).

Today, the usage pattern is as follows. Arable land is now only used on around 20 % of the terrace areas. However, this number must be interpreted with caution, since there are no longer any arable terraces on most of the historical terraced areas that are still farmed today (see the text section "Disappeared and built over"). The calculated number only answers the question of how the areas that were covered by terraces 100 years ago are used today.

As for the current main use, grassland use now predominates on almost half of all historical terraces (47 %). At around 16 %, the proportion of forest has increased significantly over the past 120 years. The proportion of fallow land and orchards has decreased (from 28 to 5 %) in favor of built-up, sealed areas and other uses.

No Data Found

Fig. 17:

Current land use on the lost terrace areas [in %]

The preceding diagram (Fig. 17) is intended to illustrate how the areas that were once terraced but were then leveled are currently being used. As expected, around three quarters of these former terraced areas are now designated as intensively used agricultural areas, for which the removal of the terraces has probably opened up more rational management (40 % arable land, 35 % grassland). Further 4.5 % of the loss areas are now built on and almost 8 % are used intensively for other purposes (“other”), e.g. as weekend, holiday home, allotment gardens, green areas and as agricultural and forestry premises, i.e. areas on which terracing may have stood in the way of optimal use. At least 9 % are forested today and 3 % are covered with field shrubs, orchards and succession areas. They are therefore currently subject to comparatively extensive use. In retrospect, the removal of the historic terraces does not seem to have been particularly effective here.

Video 2:

Terraced southern slope in the Ochsengrund near Erlau (Stadt Schleusingen) with various succession stages of forest, bracken and semi-arid grassland (rock substrate: Lower Buntsandstein)

Drone video: A. Geier (7/2022)

- Disappeared and built over: Results of a current inventory

Like all human structures, terraced landscapes are not made for eternity. Nevertheless, they can survive for centuries after the traditional uses under forest or grassland have been abandoned. Otherwise the situation would probably be much more deplorable than it is today. Townscapes and landscapes in Thuringia are still characterized by terraces. However, this impression is not always immediately recognizable when passing through; but it often helps to get an overview from vantage points or to study aerial photos and DTMs. Then it turns out that even today there are many more terraced slopes than the casual observer realizes.

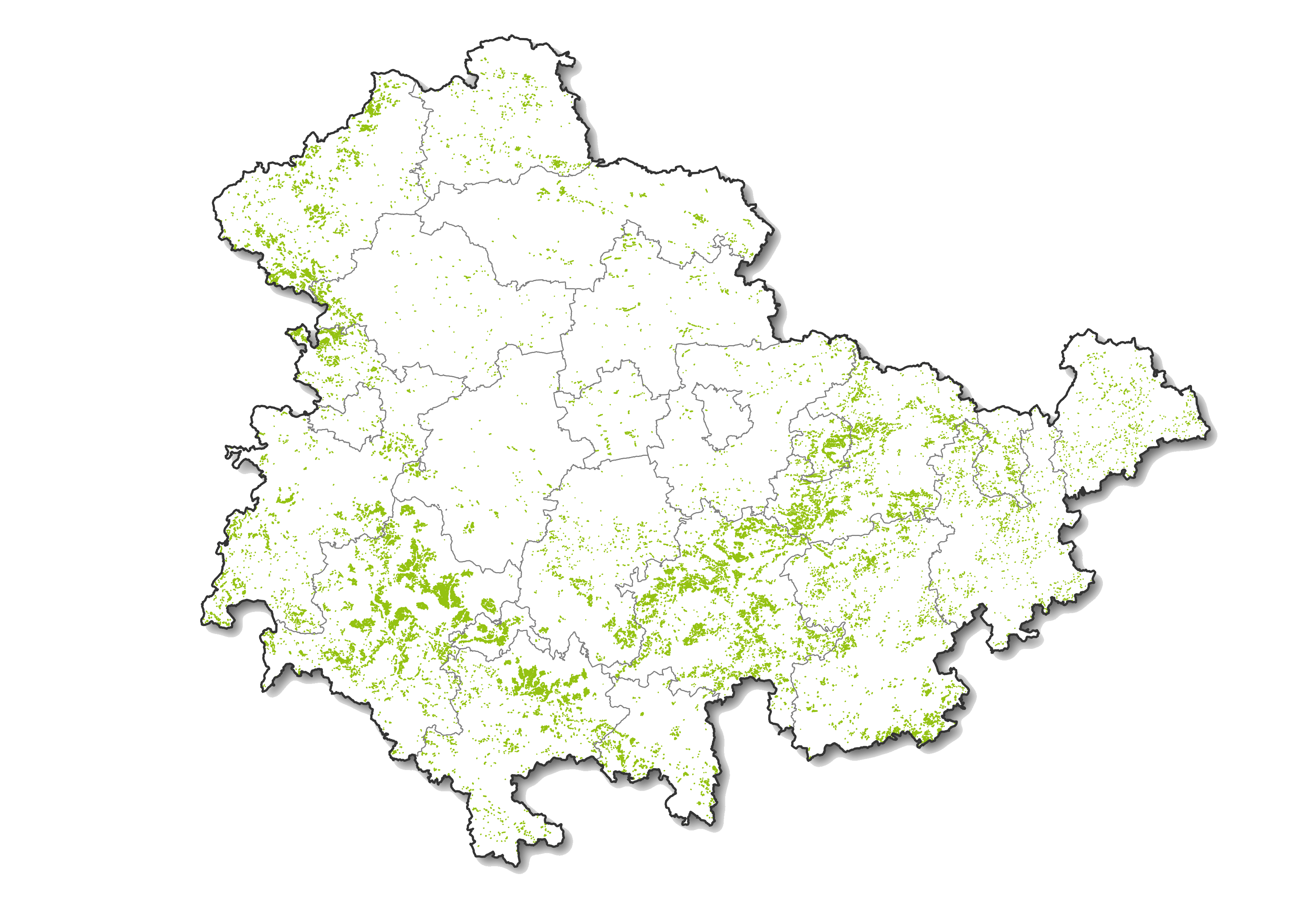

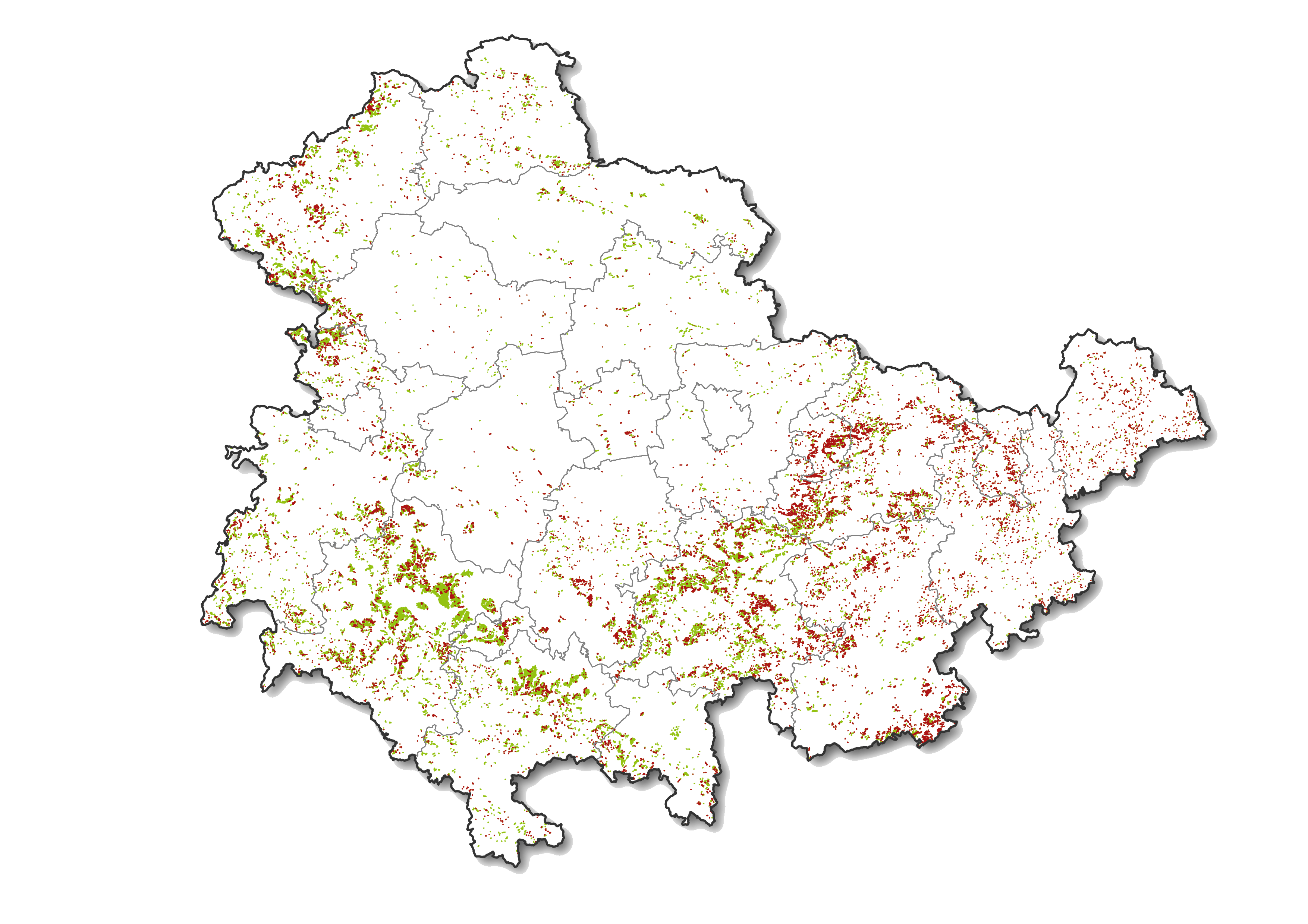

At first glance, the terrace heritage does not appear to be under acute threat. The statistical analysis, on the other hand, shows a different picture (Fig. 13). According to this, around 30% of all historical terraces have been lost since the beginning of the 20th century. From a regional perspective, there are also very large differences (see Fig. 18).

Fig. 18:

Losses of historic terraces in Thuringia since the beginning of the 20th century (green: existence at the beginning of the 20th century; red: losses to date)

after HMTB 1 : 25,000 and DGM2 ©GDI-Th

The map is based on terrace polygons that were digitized from the historical survey table sheets (as of the beginning of the 20th century). Subsequently, these polygons were projected onto the current digital terrain model (DTM2) and subsequently all those polygons were deleted in the area of which terrace steps are no longer recognizable today. This results in an approximation of the real loss situation.

As the map shows, the historic terraces in the valleys of the Thuringian Forest and their foothills have largely been preserved. That corresponds to the expectation. A targeted removal of terraces would make neither economic nor ecological (soil erosion) sense here. In addition, the interventions in the solid rock would have involved a great deal of technical effort. Therefore, the transfer to meadows and pastures or afforestation were the preferred means of choice, a large remainder succumbed to succession and gradually disappeared under a blanket of small trees and shrubs.

On the other hand, losses of terraced land can be seen above all in hilly landscapes with low to medium slope gradients. These are all areas that are currently used for agriculture on large plots and where a redesign could be carried out easily and inexpensively. The soft and easy-to-level clay soils of the “Röt”-formation and loess soils are particularly affected. The map shows heavy losses, for example, in the valley areas north-east of Jena, north of Köstritz, in Altenburger Land, in the Orla valley west of Neustadt, between Saalfeld and Kamsdorf. The terraced areas on the plateaus of the Thuringian Slate Mountains have also become significantly fewer. Here it is above all the arable soils in the deep, loamy and easily leveled weathered layers where many historical terraces have disappeared since the melioration of the GDR era, e.g. west of the Schwarza valley, between the Sorbitz and the Saale valleys and in the region around Hirschberg and Gefell.

In the urban agglomerations there were also significant structural overprints: In Suhl, Zella-Mehlis, Schmalkalden and other cities, large terraced areas have been covered with new housing estates, garages and allotment gardens since the days of the GDR. This trend continued during the construction boom of the 1990s. New terraces were even created locally, on which the typical residential areas of the post-reunification period with their geometrically planned residential streets and rows of houses including private gardens have found space.

- Overall, the following statistics result from the current inventory:

Photo 14:

Pragmatic conversion of historical terraces through residential development and garages in Königsee

Photo: H.-H. Meyer (8/2022)

- Worth seeing: Current and historical terrace locations in Thuringia

In individual sub-regions of Thuringia, terraces have shaped the landscape for centuries and in some cases still do today. The following is an overview of the most important of these “terrace landscapes”; the most interesting places in this landscape from a tourist and technical point of view are then examined more closely in the map interpretations of the detailed studies.

- Was sind uns Terrassen wert und was können Landschaftspflege und Naturschutz zur Erhaltung beitragen?

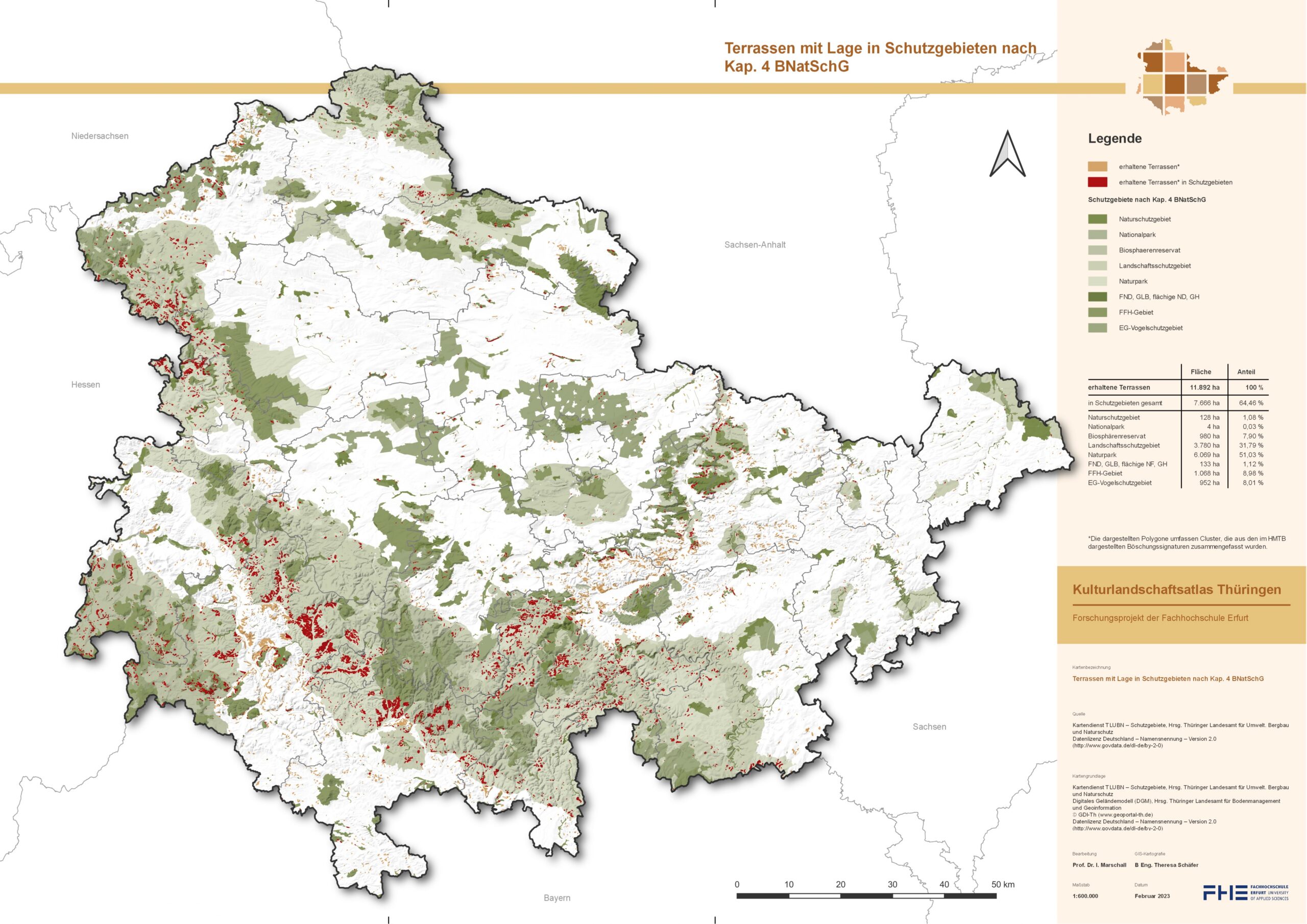

Terraced fields are characterized by numerous special features that make them count to the cultural landscape elements with the highest need of protection.

On the one hand, they are a landscape-defining part of the traditional cultural landscape. Its testimony to agricultural and local history is high. Terraced fields tell of the hard work and meager way of life of the population on marginal sites. They also document historical field structures and management systems.

On the other hand, they have a large biotope diversity. While stony ledges and dry stone walls provide a habitat for rare xerothermic plant species, on the fine-grained, flat areas tree species that are prone to budding, such as hazel, hornbeam, willow, aspen or rowan, often grow. Their multi-stemmed or bush-like growth forms are related to their former coppice-like use. The spectrum of vegetation is supplemented by thorn bushes such as roses, sloes or hawthorns, evidence of former grazing. They were not eaten by the cattle. Terraced fields thus contain all the feeding and refuge areas for many endangered animal species (mammals, birds, reptiles, insects, etc.).

Fig. 19:

Terraces located in protected areas according to Chap. 4 BNatSchG

Quellen: Hist. Messtischblätter 1 : 25 000 und DGM2 ©GDI-Th

The comparatively high proportion of terraced areas in protected areas corresponds well to the high worth of protection of the Thuringian terraced landscapes (according to Chapter 2 BNatSchG; see Fig. 19). However, as a rule, the historical value of the terraces is not the primary reason for protection, but their biodiversity caused by structural diversity and extensive use may have been decisive.

Terraced fields are locally and regionally among the endangered elements of the historic cultural landscape. Many had already fallen victim to extensive land consolidation and relief improvements during the GDR era. After the social and political turnaround, this trend continued, especially since the economic pressure to rationalize has increased even further and this is associated with the retreat from marginal income situations like never before.

Against this background, special attention should be paid to the protection of the terraces and to their professional maintenance and care. Above all, long-term and sustainable usage concepts are required that are ecologically sensible and economically viable in order to preserve the specific open-land character of these parts of the cultural landscape.

If the original condition were to be preserved, the long-abandoned forms of smallholder farming would have to be reintroduced. Ideally, that would be by using as arable land. But they also remain optically present under pastureland apparently for a long time, even if the steps gradually flatten and dissolve due to soil erosion and cattle treading (cattle walking, erosion channels). On the other hand, if they are abandoned, they are subject to succession and become increasingly overgrown with bushes or forests. It is therefore necessary to keep them open as far as possible, but in view of the high level of maintenance required, this is only possible via contractual nature conservation or agricultural support programs (e.g. KULAP).

In detail, the following model would result: Lean, species-rich ranges should be kept free from bush succession. In addition, by adding stones, you can try to stabilize the ranges endangered by erosion and flattening and at the same time promote the pioneer-like plant communities of the stone blocks and heaps.

Existing complexes of hedges or field trees on the ranges are to be cared for and – analogous to traditional firewood production – developed into a low or medium forest-like hedge. Areas that are already forested to such an extent that it makes little sense to return them to open land should be left to their own devices in terms of development.

Photo 15:

Historical terraces with meadow use on the northern slope of the Schäfergrund in Erlau (city of Schleusingen). Tree succession on the Rangen (rock subsoil: Lower Buntsandstein)

Drone photo: A. Geier (7/2022)

Ideally, extensive used fields could alternate with arable land and species-rich extensive grassland (field grass rotation) on the terraced areas. Orchard stocks should be preserved. In the case of new plants, it is important to ensure that only native varieties are planted. On small areas, the cultivation of medicinal, aromatic and spice plants, but also spelt and buckwheat would be interesting alternatives. This could also be funded by KULAP.

Grazing can also take place. In principle, only extensive grazing with light-weight animals, especially young cattle, possibly also with sheep or goats, can be considered.

A regional marketing system could be set up in selected areas with the cultivation of hedges and field shrubs for firewood and timber, fruit growing, the use of honey, berries, herbs, buckwheat or spelt, sheep meat and goat milk. Because of this and the structural richness of the fields (moving, scenic terrain forms, extensive grassland, woody structures), terraced landscapes are also attractive to tourists. This applies in particular to the extensive and well-preserved terrace complexes of the south-western Thuringian Forest and its foothills (Fluren Gießübel, Heubach, Schnett, Biberau, Erlau, Silbach).

- Picture gallery

Drohnenfotos: A. Geier (7/2022)